How I, a sickle cell anaemia woman, hydrate myself intravenously at 36000 feet

Dorothy Amanor-Boadu SRN SCM

The Elite Nursing Agency & Health Promotion Centre P O Box AN 6519, Accra-North, Ghana. [Email: elitensg@yahoo.co.uk]

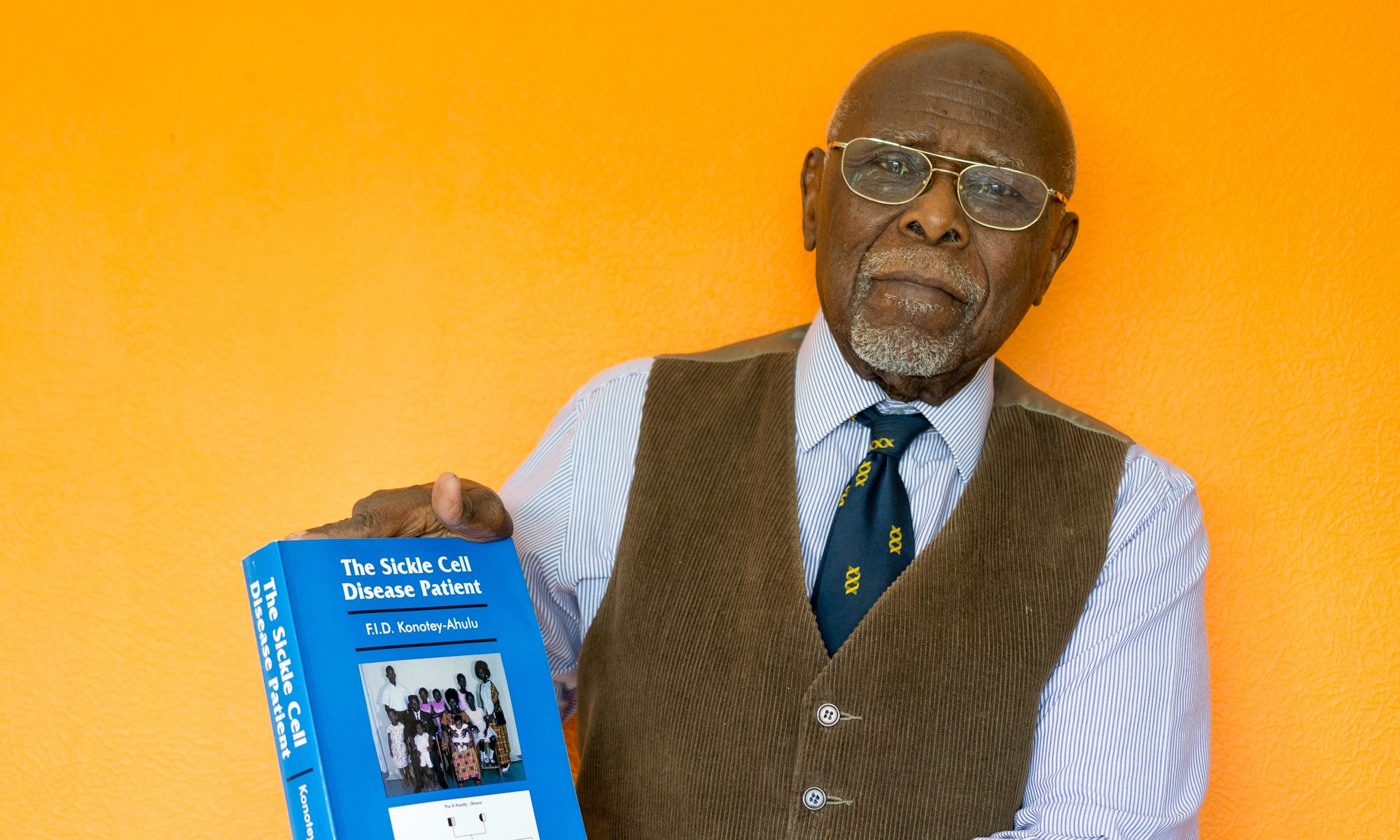

I was born with sickle cell anaemia [‘SS’]. My health, which had been pretty stable until a serious sickle crisis was precipitated by (I am embarrassed to say this) a dietary indiscretion – overeating. This first severe crisis happened at the age of 21 when I was a nurse at the Nursing Training College, Korle Bu Hospital, Accra, and almost cost me my life. If it had not been for the expertise and dedication of my doctors Dr. F.I.D. Konotey-Ahulu and Dr. Alexander Bruce Tagoe who stayed on duty for 3 days with no rest, I would not be here to write this story.

They did not go home during my critical stage complicated by thrombo-embolism brought on after a ‘cut down’ on my right ankle, performed due to inability to find any veins during the crisis. I was in hypovolaemic shock. Overeating is a known precipitating cause of sickle cell crisis

[1]. I went on to qualify as a State Registered Nurse in 1976, and worked as a Staff Nurse in charge of the Dermatology Department and Institute of Clinical Genetics Sickle Cell Clinic at Korle Bu Hospital for a little over a year. I was specially chosen to work with the sickle cell patients because my doctors thought I could empathise with them, which I did. When they were in pain, I identified with them, and wiped their brow.

I then left for the UK, a cold country, where I underwent Midwifery training at the Jessop Hospital for Women in Sheffield. I chose to do midwifery in addition to my SRN, because my mother was a well-known midwife in Accra. After this, I proceeded to the USA to specialise in Oncology Nursing, and even wrote a book

[2]. In the USA, I began to have about two hospital admissions per year for sickle cell crises with hospitalisations lasting up to 10 days at a time. All other crises occurring approximately every three months or so, lasting up to four days, were treated at home. I am now over 50 years of age, but from 1992 or thereabouts, my health gradually, but noticeably declined progressively resulting in more frequent and more severe episodes of crises. This could be dated from when I (foolishly) indulged in overeating again and ended up with an extremely severe crisis in Georgia. During this crisis, I developed a bedsore on the heel of my left heel in less than 18 hours of admission; in fact, it occurred while still in the emergency room! This crisis, occurring after I had left the restaurant with my husband and daughter where we had all enjoyed a Chinese dinner, was the second most severe in my life. [I had been taught to look for a husband who was ‘AA’, and I found one, and we have a daughter with ‘AS’ Haemoglobin Type, just like my parents]. Within 4 hours after the Chinese dinner, I presented myself at the emergency room in severe pain all over the body. Being a nurse, I often directed the doctors what to do. Quite a few times I asked them to ring Dr Konotey-Ahulu in London who would always ask the doctors to listen to me [Oh the wonder of Mobile Phones! Felix was always contactable].

I had never encountered any problems with flying on the ‘long haul flights’ (e.g.6- 9 hours from Ghana to UK/ USA and vice versa) until I reached the age of 40 years; then ‘all hell broke loose’.

Crises became even more frequent. I found it difficult to avoid the precipitating causes like late nights and (dare I say it?) too much good food.

Blood vessels for intravenous fluid (not blood usually) in crisis became more and more difficult to find, so a central venous access device was implanted into my chest which connects to a major blood vessel (superior vena cava) which, when in use, permits blood to be drawn from, and administration of intravenous drugs and fluids (drip). The device is also known as a ‘portocath/infusaport’ (depending on brand inserted). I have had this device over the past fifteen (15) years or so (each device being surgically implanted and removed/changed should infection, leakage or blockage be noted). Mine has been changed five times so far at an interval of every 2- 5 years. My port was initially inserted following an extremely bad crisis where I went into shock and no peripheral veins could be found anywhere on my body including my feet; any line obtained infiltrated within less than 12 hours. Finally, an intravenous (IV) line was inserted into my neck (central line) as a temporary measure until the port was inserted. (This is generally done in the operating room with a mild general anaesthetic or in the radiology procedures lab/room under fluoroscopic guidance with ‘twilight sleep’ induced (awake, but not fully aware)).

It was not until I went to live in the USA that I decided I had had enough of going to hospital for every crisis not resolved by oral hydration and Paracetamol, or other stronger analgesics. In the USA I found patients could come on a daily basis for intravenous drugs to be administered using the same IV site for up to 3 days or more by attaching a ‘heparin well’ to the butterfly or angiocath.

This gave me the idea of having this venous device inserted for me so I could have my intravenous fluids (drip) administered in the comfort of my own home, rather than on the hard emergency room stretcher and be charged $250.00 per hour for those uncomfortable facilities!

Having convinced my physician (who in America were haematologists) to agree to this, I treated most of my crises at home, administering the IV fluids and drugs knowing I could go on admission with a call to my doctor, if I thought things were not progressing well or I could no longer cope. With the use of the ‘hep well’, I would go to the emergency room to have it inserted (and labs drawn as ordered) and return a few days later when better to have it removed. After the hepwell other venous access devices were developed over

the years, including the ‘Hickman Catheter’ (catheter surgically inserted into a major vessel protruding through the skin with catheter hanging out on the surface), and the ‘Port O Cath’ which is a central venous access device surgically implanted under the skin in the areas of the chest, arm, or groin. I acquired my first one in 1990. When not in use, it cannot always be seen, but since I do not have too much adipose tissue to hide it, mine protrudes, and looks like a little round lump under the skin – I call it my 3rd breast!

This device allowed me to avoid emergency room visits even more. I could now access (stick) myself with the ‘Huber needle’ and hook up my drip without assistance. All I had to do was call my doctor to let him know I was in trouble (i.e. in crisis) and he would call in my prescriptions to the hospital pharmacy. My husband would then pick them up and bring them to me at home, thus bypassing the Emergency Room altogether. Being a nurse, and working in the Haematology/Oncology areas, had really become useful to me in my personal life.

To think that if it had not been for Dr. FID Konotey-Ahulu and Dr. K.A Gbedemah my parents would not have allowed me to become a nurse as the latter thought the profession could prove physically taxing! I am glad I did nursing.

At this stage, I would like to acknowledge the following specialists: Dr. Jeffrey Giguere, in Greenville South Carolina, Dr. Laura de Castro, Durham North Carolina and Dr.Melanie Jacobs, Atlanta Georgia with gratitude for the trust and confidence they had in me to permit me to treat myself with minimal supervision, and without fear that I might become a drug addict and abuse the use of the port.

Well, back to our topic. After having flown on numerous occasions back and forth from the UK to USA and Ghana without incident (the planes by then were all using pressurised cabins and later prohibited smoking also which was helpful), I noticed after the age of 40 that on flights I was now tending to start ‘sickling’ approximately 3-4 hours into the flights. I was advised by Prof. F.I.D. Konotey-Ahulu to hydrate more before and after flights, to eat only a light meal prior to and during the flight, to move about more, and to start using Aerobic Oxygen 15-20 drops to a glass of water three times a day [3], which of course I drink on flights also. Following this advice and to make sure I got through without problems and inconvenience, I requested clearance from the medical department of the carrier I used most frequently (British Airways) for oxygen to be made available to me on the flights and permission for me to administer intravenous (IV) medications and fluids should it become necessary.

This procedure meant my physician and I had to complete a medical form which basically identified my condition and my requirements for the flight (oxygen for which an additional non-refundable charge of $150.00/£200.00 is required) and the physician’s opinion as to my fitness for the flight with confirmation that I did not need to be accompanied. With the assurance that I was a nurse and could take care of myself without assistance, the airline has to date always agreed to my requests.

After travelling yearly over a period of about 4 years, my physicians no longer have to fill forms for my medical clearance – a simple telephone call to the airlines medical division in London, U.K with confirmation of flight itinerary results in a printout attached to my ticket informing airline staff of my diagnosis and requirements always sufficed [Oh thank you British Airways! (and I hope I am not accused of advertising)]. I also request seating at the bulkhead/window (least inconveniencing to other passengers, should drip be required, also more legroom and space to manoeuvre in economy class).

During packing for my intended flight, included in my hand luggage is at least 1-2 litres of IV Fluids, Infusion sets, Syringes of different sizes 10/5/3ml with and without needles, Luer lock caps, adhesive tape, tegaderm dressing, normal saline and heparin flushes, alcohol swabs. Medications as prescribed including tablets and injection Phenergan, Pethidine, Paracetamol, Airtal or Percocet. One or two bottles of IV Ciprofloxacin and a small ‘sharps/biohazard’ container for disposal of needles and glass ampoules are also packed.

Finally, a letter from my physician giving reasons and the need for my possession of needles, lest some busybody security person suspect me of being a terrorist! Just a word here about my experience with pain killers on 3 continents. In Africa, neither Morphine nor Diamorphine are used for sickle crisis. In the USA Diamorphine is banned for clinical use. In the UK, both Morphine and Diamorphine are used for sickle cell crisis. In Ghana, we find Diclofenac, Airtal, and Ketorolac, with plenty of hydration, and occasionally Pethidine very briefly, more than adequate for the severest of crises.

Should I be flying with a carrier whose arrival and departure times are not always reliable a call to the airport to verify that flight is likely to depart on time is made. My goal here is to administer my intravenous fluids no more than an hour before checking in time to ensure adequate hydration for the flight. I have on occasion had to have my flight rebooked due to constant changes in flight departure time. Original departure of one airline that shall remain nameless was for 8pm, changed to 10pm, then 3am. Finally, the plane left without me at 5am. I took the flight 2 days later to get my hydration time right! The moral for other patients reading this article is this: ANTICIPATE PROBLEMS, AND PLAN HOW TO COPE WITH THEM! If necessary, cancel agreed plans (like a flight) in order to save your life.

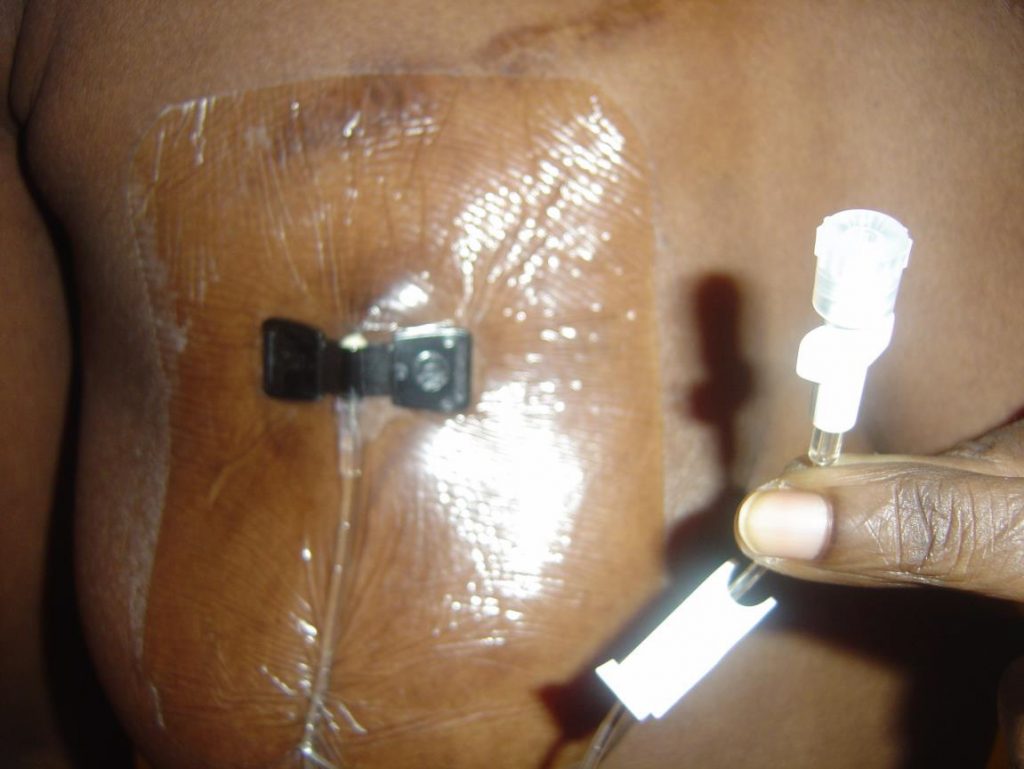

My normal procedure now before any flight is to pack my bags about two weeks prior to the departure date (generally reduce stress – physical/emotional as much as possible several days/weeks before flight, and increase oral hydration three days before departure). On the date of departure I check in early where possible, return home to rest, take a bath prior to inserting my Huber needle into the centre of the port after cleaning it and an area of approximately 2” circumference with Betadine and alcohol swabs, using sterile technique secure/cover with appropriate dressing – Tegaderm/biocclusive (usually 3”x5”-this is a water repellent dressing applied to secure and protect port from invasion of pathogenic organisms etc) [Picture]. It is possible to shower/bathe without the insertion site becoming wet. Dressing change is required every third day and as necessary. Huber needle (90-degree angled needle) should be changed every 7 days, but should be removed as soon as no longer required for use to avoid risk of infection.

Once ‘hooked up’ I administer 500-1000ml of Dextrose/Saline or Normal Saline over 2-4 hours depending on total amount to be given and how I feel at the time. On completion, the Port is flushed with 10ml saline and 3ml U100 heparin flush, then capped and extension tubing tucked into my ‘bra’. IV infusion/tubing capped off and stored in a new clean self-sealing plastic bag, which is then added to my hand luggage.

Once on board the flight, with any signs of sickling (pain/discomfort) I first request for oxygen which, is either piped directly to my individual seat (from the cockpit) or via small portable tanks supplied by stewardesses. This is administered at 2-4 Litres/min depending on how acute the distress is. After 20 minutes or so, if no relief of symptoms are noted I inform the stewardess of my intent to administer IV Fluids and drugs, and request for a clothes hanger. (Usually at this point there is panic amongst the Air Crew because, despite the clearance printout from the medical department and the Ground Crew having all the details and specifics, the aircrew generally are left with only minimum information such as “they have a medical on board”).

At this point I usually get a visit from the Captain and Chief stewardess. Once everyone gets the fact that there was some miscommunication, I proceed to hang and prime the infusion tubing. The hanger is used to hang the infusion onto an appropriate fixture in front of or above me. Occasionally, depending on location of seat adhesive tape may be required to secure drip at a height to promote gravity drainage. Since the port is already accessed and ready for use all that is required is to flush the extension tubing with saline prior to administering IV medications and hooking up the infusion. Once the rate for infusion is regulated, a little nap with continuous oxygen usually averts any major crisis occurring even if not totally resolved. Most of the time, oxygen is not required for more than 2 hours and IV for 4 hours.

My IV line can be disconnected, flushed and capped off when I feel I no longer need it or at least thirty minutes before landing. To date there have been no complaints or concerns from other passengers. Everyone, crew and passengers alike have been considerate and helpful – willing to change seats where needed.

So now you know how Intravenous fluids can be safely and conveniently self- administered at 36000 feet!

Competing interests: None declared.

Acknowledgement: I thank Professor F I D Konotey-Ahulu for urging me to tell this story to encourage sickle cell disease patients never to give up.

1 Konotey-Ahulu FID. The sickle cell disease patient. Natural history from a

clinico-epidemiological study of the first 1550 patients of Korle Bu Hospital Sickle Cell Clinic. Watford, Tetteh-A’Domeno, 1996, page 122.

2 Amanor-Owusu D. Cancer Chemotherapy Manual. Legon, Accra. Ghana Universities Press, 2002

3 Konotey-Ahulu FID. Sickle-cell disease and the patient. Lancet 2005; 365: 382-83

Legend: Accessed Port covered with Tegaderm dressing. Note pallor of my nail: I have sickle cell anaemia with a cruising Haemoglobin level of 8 grams/dL.

Submitted by:Dorothy S. Amanor-Boadu