Current “hit and miss” care provision for sickle cell disease patients in the UK

Following her article [1] on NCEPOD [2] Susan Mayor has, again, produced a succinct summary [3] of the recent publication of ‘Standards’ on the care of patients with sickle cell disease (scd) in the UK [4], written by a multidisciplinary working group chaired by Consultant Haematologist Dr Ade Olujohungbe. The public launch of the publication was on 9 July in the House of Commons where the Archbishop of York, Dr John Sentamu, said: “These Standards are another step in providing consistent care” [3].

HIT AND MISS CARE PROVISION

Hitherto, consistent care has not been UK’s strong point. The description by the ‘Standards’ Group’s chairman, Dr Olujohungbe who, in my opinion, has proved to be the most experienced Clinical Haematologist in the UK on the scd patient since Hammersmith Hospital’s Professor Lucio Luzzatto with whom Olujohungbe was closely associated, underlines what Graham Serjeant [5] and I have bemoaned for years. Olujohungbe said “The care provision for sickle cell disease is currently hit and miss, depending on the attitudes and experience of health professionals” [3]. This sad diagnosis by the leading UK haematologist on the scd patient was precisely why “NCEPOD found that many patients died of complications caused by excessive doses of opiods” [1, 2].

RESPONSE OF TEN DOWNING STREET

During the week when UK media (radio, television, & newspapers) were full of news that the Prime Minister was inviting personal phone calls and contacts on people’s concerns I took the opportunity to write to The Right Honorable Mr. Gordon Brown drawing his attention not only to the publication of the NCEPOD Report [2], but also to the international responses that were beginning to pour in [6]. The reply I got, dated 25 June 2008, from Ten Downing Street was encouraging: “Dear Dr Konotey-Ahulu – The Prime Minister has asked me to thank you for your recent letter and enclosures. Mr. Brown has asked that your letter be forwarded to the Department of Health so that they may reply to you on his behalf. (Signed) MR R SMITH”.

RESPONSE OF THE DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH

I looked forward eagerly to answers to the 3 questions I posed in my correspondence, namely (i) With respect to scd patients dying with overdose of opiods (heroin & morphine) in their blood “What kind of supervision led to this?” [6a] (ii) Why should West Indians and West Africans who did without morphine in their countries be put on morphine pumps when they were admitted to UK hospitals? [6a] (iii) To those UK haematologists who say “unbearable pain is unbearable pain, which must be treated with the most potent analgesic drugs known” I posed this third question, how many of them would prescribe diamorphine (heroin) monthly for their teenage daughters whose dysmenorrhoea was simply unbearable? [6a]. The Department of Health wrote back to me Ref; TO00000325139 dated 16 July 2008. Signed by “Shelley Wilson, Customer Service Centre”. All the questions were totally ignored. Would the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) now provide specific answers to these my 3 questions?

OUR GENETIC FUTURE

Africans, African-Caribbeans, and African Americans must wake up and realize that their genetic future depends on themselves, and not on any Department of Health. We must reduce the genetic disease burden, starting now, otherwise their children will continue to be subjected to “hit and miss” health care provision, ending up on heroin and morphine pumps. “Unless we Africans are involved in genetic counseling” and voluntary family size limitation (GCVFSL), I said not long ago “the genetic burden on the National Health Service will go up and up” [7]. What is more to the point, unless we take this very seriously our children and grand children will suffer greatly from scd [ACHEACHE syndrome], for “one in three West Africans in the UK has a beta-globin variant gene (ie NORMACHE) whose unsuspecting owner needs to be identified and helped with genetic counseling and family size limitation” [7]. Those who do not quite believe the enormity of the NCEPOD Report [2] should, please, start by taking a good look at how the rest of the world regards the “hit and miss” approach to the present care of sickle cell disease patients in the United Kingdom [6a-6j].

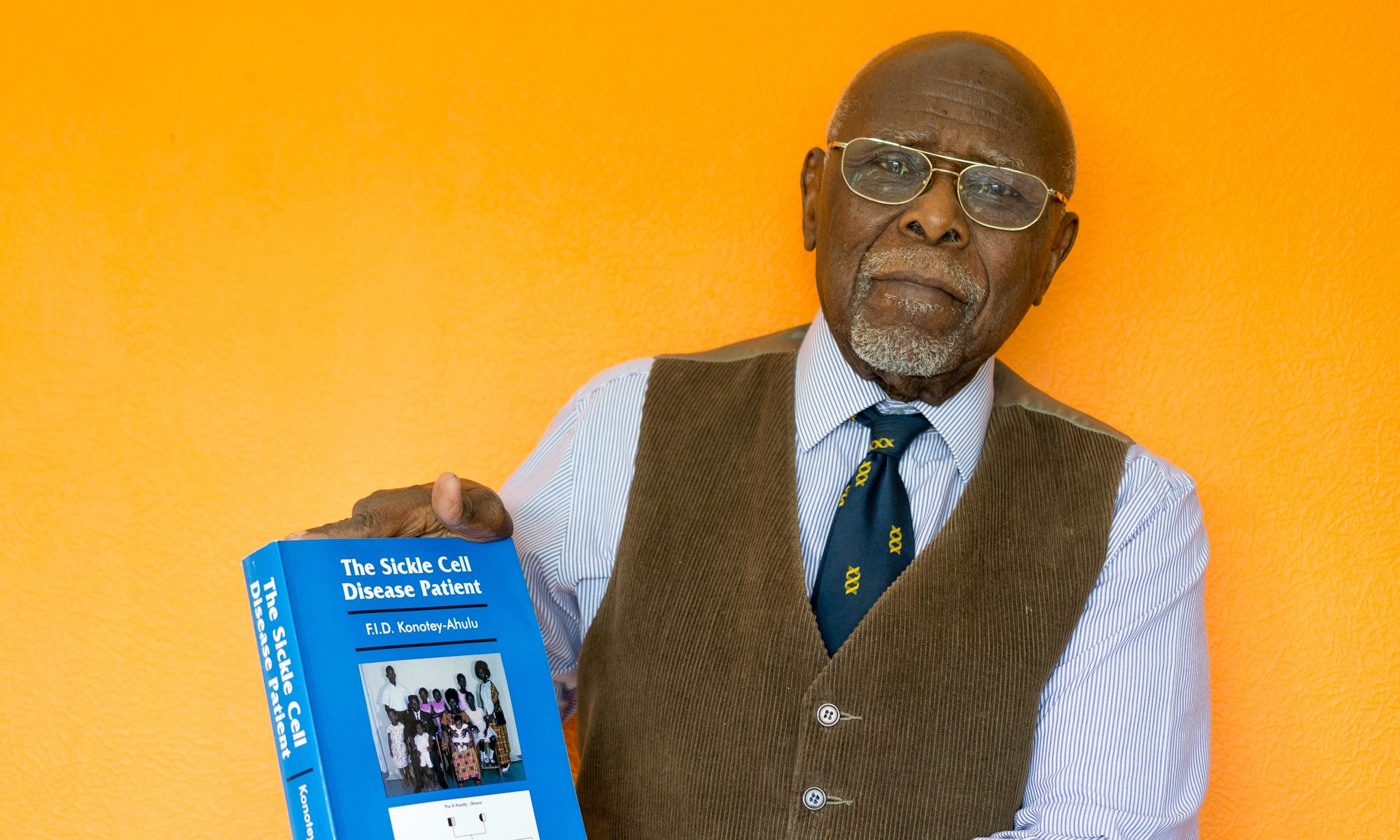

Felix I D Konotey-Ahulu MD(Lond) FRCP(Lond) DTMH(L’pool) – Kwegyir

Aggrey Distinguished Professor of Human Genetics, University of Cape Coast, Ghana and Consultant Physician Genetic Counsellor in Haemoglobinopathies, London W1G 9PF.

felix@konotey-ahulu.com

1 Mayor Susan. Enquiry shows poor care for patients with sickle cell disease. BMJ 2008; 336: 1152

2 NCEPOD (National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death) Sickle: A Sickle Crisis? (2008) [Sebastian Lucas (Clinical Co- ordinator), David Mason (Clinical Co-ordinator), M Mason (Chief Executive), D Weyman (Researcher), Tom Treasurer (Chairman)] info@ncepod.org

3 Mayor Susan. Group publishes standards for adult sickle cell disease to reduce number of unexplained deaths. BMJ 2008;337:a771

4 Sickle Cell Society (London) The Standards for the Clinical Care of Adults with Sickle Cell Disease in the UK. http://www.sicklecellsociety.org

5 Serjeant GR. The case for dedicated sickle cell centres. BMJ 2007; 334: 477 (3 March)

6a http://www.bmj.com/cgi/eletters/336/7654/1152-a#196224 [Felix I D Konotey-Ahulu 29 May 2008] Poor care for sickle cell disease patients: This wake up call is overdue

6b http://www.bmj.com/cgi/eletters/336/7654/1152-a#196359 [Kwabena Frimpong-Boateng 30 May 2008] Re: Poor care for sickle cell disease patients: This wake up call is overdue

6c http://www.bmj.com/cgi/eletters/336/7654/1152-a#196514 [Marianne Janosi 3 June 2008] “Poor care for patients with sickle cell disease” BMJ 24 May 2008 Volume 336.

6d http://www.bmj.com/cgi/eletters/336/7654/1152-a#196520 [Cecilia Shoetan 3 June 2008] I lost my Sickle Cell disease adult daughter minutes after being given Diamorphine intravenously when she could not breathe.

6e http://www.bmj.com/cgi/eletters/336/7654/1152-a#196631 [Frank Edwin 5 June 2008] Re: Poor care for sickle cell disease patients: This wake up call is overdue

6f http://www.bmj.com/cgi/eletters/336/7654/1152-a#196848 [Ivy Ekem 9 June 2008] Care for sickle cell patients

6g http://www.bmj.com/cgi/eletters/336/7654/1152-a#197301 [Mawunu Chapman Nyaho 17 June 2008] Poor care for the sickle cell disease patient: “Pain won't kill him, but Morphine could”.

6h http://www.bmj.com/cgi/eletters/336/7654/1152-a#197350 [Emmanuel Jeurry Blankson 18 June 2008] Sickle Cell Disease is managed, NOT treated.

6i http://www.bmj.com/cgi/eletters/336/7654/1152-a#197377 [Yolande M Agble 18 June 2008] Re: Poor care for sickle cell disease patients: This wake up call is overdue.

6j http://www.bmj.com/cgi/eletters/336/7654/1152-a#198669 [Akosua M Dankwa 11 July 2008] Sickle Cell patients deserve to live.

7 Konotey-Ahulu FID. Need for ethnic experts to tackle genetic public health. Lancet 2007; 370: 1826 (December 1)

Competing interests: I come from a sickle cell disease (scd) family, my parents were traits (NORMACHE), and I am actively involved in genetic counselling to reduce the burden of sickle cell disease (ACHEACHE) in future generations.