BMJ 2007;335:210-211 (28 July), doi:10.1136/bmj.39268.553021.47

Views & reviews

Personal views

The perils of unmasking scientific truths

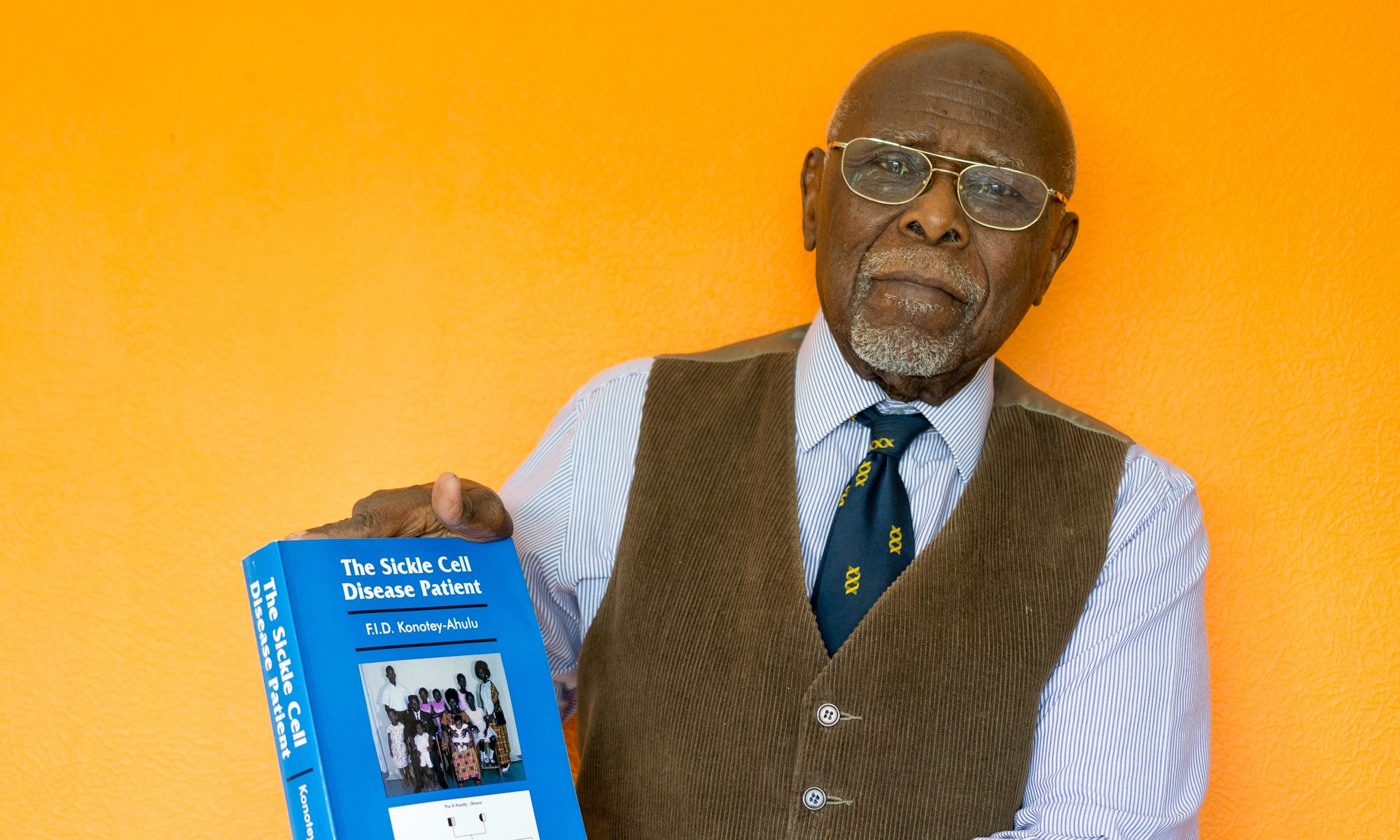

Felix I D Konotey-Ahulu, consultant physician

To be chosen to deliver the keynote address at the Martin LutherKing Jr Foundation's award banquet took me completely by surprise—andto find that four bodyguards had been assigned me shook me rigid.Nobel laureates Linus Pauling and Max Perutz, along with HermannLehmann, Roland Scott, A C Allison, Graham Serjeant, and I,were among a select few invited to

Was it, perhaps, because a foundation commemorating a blackperson wanted to “show off” the only black African among thosereceiving the award? Was it, perhaps, because I was then directorof the largest sickle cell disease clinic in the world? Or wasit because I was the only person to have traced hereditary diseasein his forebears, with named patients, generation by generationback more than three centuries? Or was it the statement madea few weeks back in

Such “perhaps hypotheses” competed in my brain when I arrivedin

The award organisers, who came within minutes of my call, explainedthat the text of my lecture alerted them to several problems.I had distinguished between sickle cell trait and sickle celldisease (sickle cell anaemia) because the terms were being usedinterchangeably, with disastrous consequences, by people whoshould know better. People with the trait (one abnormal gene)cope better than people with two normal genes with falciparummalaria, which kills sickle cell disease patients (two abnormalgenes) quicker than people with two normal genes. I had questionedpublished work which claimed that black Army recruits exercisingat an altitude of 4000 ft collapsed and died because of sicklecell trait. I had asked: “How could black sickle cell traitsrun and beat the whole world at the Olympic Games at MexicoCity, at an altitude of 8000 ft (double the altitude at whichpeople with sickle traits had been said to perish)?”

Why did I need four bodyguards? The award organisers thoughtI needed protection because I used data from an article by JamesBowman, who had named seven insurance companies in the

The award organisers advised me to leave names of the insurancecompanies out of my lecture. Even so, they could not run therisk that I would be bumped off before the lecture. I cannotremember being able to eat anything at the banquet, but I wasglad to be able to shake hands later with the great and good.I left

How dangerous is it these days to stand firm for scientifictruth—or rather, how risky is it to criticise scientificuntruths? The Ghanaian herbalist Nana Drobo was found with bulletholes in his head, not long after successfully treating a dyingFrench man with AIDS who was sent to him from the

Published : BMJ [www.bmj.com]